The Case For RMX Records

...or, Making it harder to forge email

I am no longer maintaining this page. You should refer to more recent work on RMX or SPF for further information.

Initial publication: 2003.May.01

Page last updated: 2003.June.02

When I first wrote this document in Feb. 2003, I intended to submit an

Internet Draft to the IETF, formalizing what is discussed here. However, I

soon discovered that a draft

suggesting practically the same thing had been proposed just two months

earlier! Hadmut Danisch had, apparently, beaten me to the punch. Well,

Hadmut, your RMX records are a good idea, so I'm posting this

document to increase awareness.

Since posting this article, I have learned about two other proposed

anti-forgery mechanisms, those of Fecyk and Vixie, which are listed in the

References section. These are functionally equivalent to RMX,

but are implemented in subtly different ways; either of these solutions

would also be satisfactory to me. Update: 2003.06.02: It seems there are

even earlier RMX-like proposals! Here's one

from David Green; he wanted to call the records MT. And Paul

Vixie mentions

that Jim Miller suggested the concept as early as 1998, although I

cannot find a written proposal.

Contents

- Abstract

- Motivation

- Introduction

- Identifying Forged Email

- The Concept

- DNS, not the web!

- Discussion

- Notes and Comments

- Ugh! This is

identall over again! - New resource records may break old versions of BIND

- Implementation requires limiting mail senders

- Will it stop spam?

- What are the implications for .forward?

- Is spam really forged?

- What about the RFC-822 From: header?

- DNS spoofing issues

- Privacy issues

- The Joe Job

- Issues for users of

dyndns - Issues for non-web users of popular webmail sites

- Epilogue

- References

Abstract

This document supports and encourages the adoption of Hadmut Danisch's

RMX resource records for DNS. RMX records are

intended to make email forgery difficult by providing a mechanism for a

domain owner to list all mail servers authorized to send email on behalf of

his or her domain name. They eliminate the most serious drawback of

SMTP--the meaningless From: header--without

breaking any core internet protocols.

Motivation

A few short months ago, I had the unpleasant experience of getting email-jacked. Apparently, someone sent thousands of unsolicited advertisements, all claiming to have come from webmaster (at) www.mikerubel.org. The messages in question had never passed through my mail server (which does not relay), and they were certainly not sent by me. They were forged. It was as if the spammer had done a mass-mailing and had printed my home address on the envelopes to lend them credibility.

The only reason I know about this episode is that over the course of a day, I received a number of bounces from recipients' vacation programs and spam filters. I traced the headers on one of the bounce messages to a machine in South Korea, which either belonged to the original spammer or, more likely, had also been hijacked by him. There was nothing more I could do at that point, so I let the matter slide.

Unfortunately, the episode was more than just annoying. Supporting the

reasonable inclination to refuse additional mail from the sender of an

unwanted message, some email programs provide a "refuse sender" feature.

But since the From: field of spam is almost always forged,

recipients end up blocking the wrong person. (For the spammers, this was

the idea all along, of course). How many computers will no longer accept my

email, I wonder?

The big sites get this all the time. I'm sure that a large fraction of your

spam appears to come from yahoo.com or

hotmail.com. You might be tempted to conclude that such sites

are major spam havens. They aren't (see here). If you check the full headers on the

messages you've received, you'll see that yahoo or

hotmail did not send them. But the misconception persists--I

know people who block all email claiming to originate from those sites!

While limiting email forgery would not, by itself, put an end to spam, it

would remove one of the spammers' more potent weapons: the ability to

masquerade as others. The constant target cyndi@hotmail.com,

for example, would finally get her name back. Robust forgery detection

might also help improve the accuracy of such powerful filters as spamassassin by providing them with

more information on which to base their decisions.

Email forgery is a serious problem. Larry Seltzer has recently gone so far as to propose replacing the whole Internet because, in his words:

"...the biggest failure in this regard is SMTP, the dominant mail protocol of the net [...] We know how to fix these problems; the problem is that doing so would break existing applications, which means email in general."

And Seltzer has plenty of company. I disagree, though; I believe that it is indeed possible to fix the email forgery problem without breaking, or even substantially changing, the Internet, and without having to change users' behavior.

Here's how.

Introduction

Throughout this document, I will refer to the From: address on

an email as if there were only one such address. Of course, this is a

simplification; there may be an envelope MAIL FROM: address, a

message From: address, and even other, more obscure sender

addresses. It is the envelope address we're interested in. These and other

details are discussed at length in the notes section.

We begin by learning how forgery works.

Every self-respecting computer geek has, at some point in the course of his

or her education, sent an email with a forged From: header.

The prank generally goes something like this:

$ telnet myfriendsmachine.college.edu 25 Trying 192.168.1.2... Connected to myfriendsmachine.college.edu. Escape character is '^]' 220 myfriendsmachine.college.edu ESMTP Sendmail 8.12.3/8.12.3; Thu, 27 Feb 2003 23:05:02 -0800 (PST) HELO mymachine.college.edu 250 myfriendsmachine.college.edu Hello mymachine.college.edu [192.168.1.1], pleased to meet you MAIL FROM: god@heaven.org 250 2.1.0 god@heaven.org... Sender ok RCPT TO: poorsod@myfriendsmachine.college.edu 250 2.1.5 poorsod@myfriendsmachine.college.edu... Recipient ok DATA 354 Enter mail, end with "." on a line by itself From: "Mr. Deity" <god@heaven.org> To: "Poor Sod" <poorsod@myfriendsmachine.college.edu> Date: Thu, 27 Feb 2003 23:05:03 -0800 (PST) Subject: some friendly advice Hello my child, I know about that stack of magazines under your bed. For shame! Repent now and free yourself from sin. Send the magazines away with your roommate. He'll know what to do with them. Yours in virtue, God ps> stop borrowing his toothbrush. that's disgusting. . 250 2.0.0 h1S7238N127934 Message accepted for delivery QUIT 221 2.0.0 myfriendsmachine.college.edu closing connection Connection closed by foreign host. $

The reason this works is historical. Email is old; SMTP is one of the

oldest protocols on the net. It was born at a time when senders could

generally be trusted to identify themselves and spam was only a serious

issue to vegetarians. At

that time, routing (now a completely automatic process) needed

application-layer help in the form of bangpaths, and the mail relay which

delivered your message was not necessarily associated with the original

source. Only the weakest of background checks--such as verifying that the

From: domain actually existed--were put in place to

authenticate the sender.

Now, of course, the Internet is a shadier and more autonomous place. The need for public mail relays evaporated just as their services began to suffer at the hands of dishonest marketers. Black-hole lists have emerged to shun sloppy sysadmins and their service providers. Stronger security measures, such as digital signatures, now provide both a means to authenticate the sender of a message and a way to prevent adulteration enroute. Despite their potential, however, digital signatures are seldom seen in email nowadays, owing mainly to the level of understanding they require of end-users.

Our apathy in this area has given rise to an unfortunate new type of

problem. Where email header forgery was once mostly the domain of bored

college students, it has now become the modus operandi of spammers,

virus-writers, and con artists. End users are understandably confused: why

should the From: address on an email header be less trustworthy

than the http:// URL in their web browser? Users tend to trust

an email if it claims to come from a friend, a co-worker, or a well-known

company. And their trust is easily exploited. Witness chain letters

claiming to originate from microsoft.com,

false security announcements claiming to originate from organizations

like Symantec or CERT, and viruses or worms such as Nimda which use

forged email headers to trick users into opening them. And witness, of

course, the torrent of forged spam currently flooding your inbox.

Identifying Forged Email

I won't attempt to outdo the cogent and extensive article on email header dissection available at stopspam.org, but we do need to cover the basic process of uncovering a forgery here.

One begins by scanning the full message headers for Received:

lines, each of which looks something like this:

Received: from foo.com (aardvark.foo.com [192.168.1.222])

by bar.com (Postfix) with ESMTP id 27Y1C46CB

for <somebody@outthere.com> Sat, 1 Mar 2003 17:25:48 -0800 (PST)

One Received: entry is added to the top of the email by every

relay the message visits on its trip across the Internet, giving the

recipient a (reversed) postal history. For example, In the situation

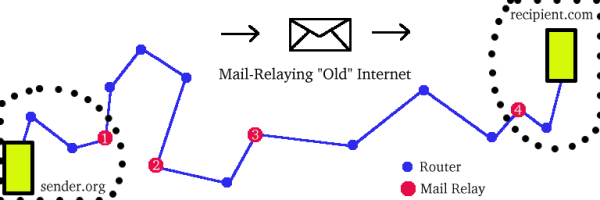

illustrated below, four headers would be added: one by the sender's outgoing

server (#1), two by the public mail relays (#2 and #3), and one by the

recipient's incoming mail server (#4).

The top Received: header will be the recipient's mail server,

which is the (real) machine he or she contacted to read the message.

Proceeding down through earlier Received: lines, the recipient

should be able to trace back to the original sender's mail server. If the

message is forged, this process breaks down at some point; one of the real,

trustworthy mail relays (probably #4, the one belonging to the recipient's

company or ISP) will have accepted the message from a machine through which

it had no reason to pass. To cover their tracks, spammers sometimes add a

few bogus Received: lines below that as well.

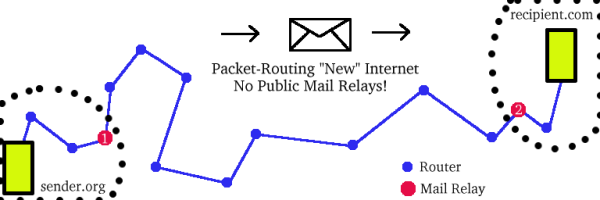

Detecting a forgery begins by realizing that email systems never

legitimately use third-party relays anymore (certain exceptions to this

rule, discussed below, are the reason forgery detection is currently an

inexact science). Now that the Internet has standardized on TCP/IP, routing

is automatic (blue dots in the picture below), and so open relays are no

longer needed. If a message is being delivered from someone at

sender.org to someone at recipient.com, then at

some point one of the sender.org mail servers will have passed

the message directly to one of the recipient.com mail servers.

Routers, not mail relays, will be the intermediaries. This situation is

illustrated below.

Thus, detecting a forgery comes down to the following rule:

To Identify Forged Email: Look back through the

Received: lines to the last trusted relay--i.e., the last relay

belonging to your company or ISP (#2 in the above picture). Check the IP

address--not the reported name--from which that relay received the message.

In the example above, this would be the IP address of machine #1. If that

IP address does not belong to the sender's netblock, then the message is

probably forged.

The reason we check the IP address instead of the name is that under TCP (a

basic protocol on which higher-level protocols like SMTP are built), the

source IP address is difficult to forge. You may use the whois

utility to determine whether the IP address of the sending relay belongs to

the netblock of the sender. Details on the use of whois would

be outside the scope of this article, but please see the References section below.

The problem with the forgery check just described is that while most sites obey this convention, there is no shortage of exceptions and marginal cases. One issue is that small sites sometimes use their hosting company's mail server, yet the business relationship might not be obvious from whois records. Also, some organizations do not (yet) provide remote authenticated SMTP services for traveling members, relying instead on laptops, which send their messages directly.

However, there is a way to make the forgery check robust, which we shall now demonstrate by way of example.

The Concept

The management of foo.com is growing tired of spammers using

its good name to promote such unsavory products as earlobe enlargement gel,

herbal spleen supplements, and sugar-free pizza. To make matters worse, a

loosely-knit group of twelve-year-old internet vigilantes has begun

peppering foo.com's customers with false safety recall notices

for its "productz". Irate customers and primary school spelling teachers

have been ringing all day, and the staff is exasperated.

A company-wide meeting is called to address the problem. Early suggestions, such as hiring one secretary's large, muscle-bound nephew to track down the perpetrators, receive widespread support but are ultimately rejected for assorted legal reasons.

Finally, a network administrator pipes up. "What if we post a page on our web site that lists the IP addresses of all of our outbound mail servers?

"Spammers can still forge our company name, but ultimately they're sending the spam from somewhere else. They can't make it appear to come directly from our servers' IP addresses unless they break into our network, which would be a lot harder. So customers will be able to check the source from which their ISP received the message (in the email header), and verify that it's one of the IP addresses on our list."

A dramatic pause ensues, during which the the entire staff contemplates the network administrator's suggestion. One-by-one, the participants seem to light up with understanding. There is a great deal of appreciative nodding and chin-scratching. Finally, the company founder stands up and clears his throat. "What the heck is an IP address?"

DNS, not the web!

The core idea of the network administrator's plan--publishing a list of the company's real outbound mail servers--is sound. But for a number of reasons, the web is probably not the place to do it. Web sites usually exist to communicate information to humans, and if this strategy is going to work, it needs to happen automatically. Also, it might not be obvious where to look; not all mail systems have associated web sites, and those that do might adopt different conventions.

Fortunately, there exists a system which is better suited to this task:

DNS. The Domain Name System is the "phone directory" of the Internet,

responsible for translating names (such as mikerubel.org) to IP

addresses (such as 131.215.118.32). DNS actually stores all

kinds of information about a name: the IP address just mentioned is called

the A record. Nameservers (NS records) provide

directory information for machines in the domain. Mail servers

(MX records) are configured to recieve its email. Each piece

of information associated with a name is called a resource record,

or RR, and is identified by a short abbreviation. To learn

more about the different kinds of resource records available, check out the

official specification, RFC 1035, which is linked-to in the references section below.

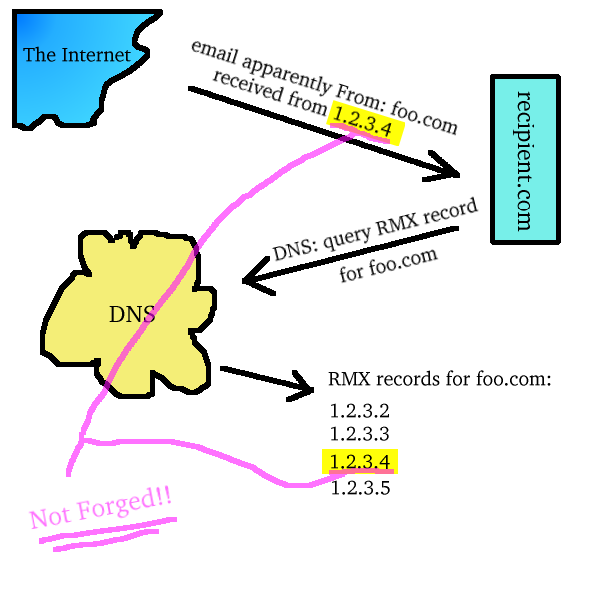

One of the first actions a system takes when receiving an email is to query

DNS for the name given in the From: address, to verify that it

actually exists. If we add one new type of resource record, tentatively

called RMX (or "reverse-MX"), for the IP addresses

of servers authorized to send mail on behalf of that name, then we're

set--the recipient's email server will verify that the sending IP address

matches one of the RMX records of the name given in the

From: address.

This process is illustrated below.

Had the actual source not been among the RMX records for

foo.com, the message would have been registered as a forgery.

Net-minded readers may recognize the reason this works: it's a type of three-way handshake, similar in principle to the one which makes it fundamentally difficult for the initiator of a TCP transaction to conceal his or her identity.

Discussion

The most significant property of RMX records is that they

do not break the Internet! The standard email protocol,

SMTP, does not change. DNS simply adds a new type of resource

record--something it is designed to do both easily and backwards-compatibly

(clarification). The protocol remains the

same. If the sender has not configured RMX records, or the

recipient's mail server does not bother to check them, then nothing changes.

However, if RMX records have been configured, and the recipient

does check them, then forgeries will be detected. What the recipient

chooses to do with that information--throwing the message out immediately,

passing it on as a special header for use by (for example) spamassassin or procmail, or ignoring it--is up to the

recipient. Without breaking the Internet, RMX records make

email forgery much more difficult.

RMX records are also attractive because they don't have to be

implemented everywhere to be useful. There is a small, incremental

advantage to upgrading to RMX-aware software, both for senders

and for recipients. Senders get some protection against the illegitimate

use of their names, and recipients improve their ability to filter spam and

avoid being deceived. This property makes the eventual widespread use of

RMX records a realistic goal.

The efficacy of this scheme rests with the security of DNS. That's an

important observation--not necessarily a drawback, because the era of secure

DNS (DNSSEC) is slowly coming--but it is only fair to note that if the DNS

system can be compromised, then RMX records break down. The

recipient's mail server must handle inability to access the sender's name

server (caused, for example, by a DDOS attack) gracefully, perhaps by

placing the message in temporary quarantine until the name server is

accessible again.

RMX is not a strong authentication mechanism, but it should be

sufficient to stop most forgery. It is not intended to replace stronger

mechanisms such as digital signatures. With RMX, the

From: address on an email will become exactly as trustworthy as

the URL in a web browser, which meshes with user expectation. Things

that ought to work, such as "refuse sender," will work.

One particularly nice feature of RMX records is that they add

to the technical infrastructure governments will have at their disposal to

apply legal and economic pressure to would-be email forgers. Domain names

could be forfeited (possibly along with a deposit) if they are used to send

misrepresented email. Or perhaps a credit-like system could be established

to prevent frequent abusers from registering new domain names.

Notes and comments

Ugh! This is ident all over again!

Fundamental difference: with ident, you call back the forger's

machine. With RMX, you call back the forgee's machine. The

former approach assumes that the forger is one user on a server administered

by someone trustworthy--which, on the Internet, is often not the case.

RMX requires no such assumption.

There seems to be a very common gut reaction to this proposal: that

RMX would be vulnerable to trivial attacks like this

one. It isn't, and I wonder if the confusion doesn't stem from a

lingering bad taste over ident.

New resource records may break old versions of BIND

Scott Nelson was kind enough to inform me that some older versions of BIND

do not properly handle unknown RR's, crashing or otherwise

failing when they receive one. While I assume that very few nameservers on

the Internet are so easy to break from remotely, it would be more accurate

to say, "RMX records are not as disruptive to the Internet as competing

approaches might be."

Implementation requires limiting mail senders

Before an organization posts RMX records, it must ensure that

all outbound mail passes through one of the designated outgoing mail

servers. Right now, certain situations, such as travel, often lead to a

break in this convention. Before an organization can implement

RMX, it must shore up these leaks. There are many technologies

now available (VPN, SMTP-AUTH, SASL, SSL/TLS, and even webmail come to mind)

which can be used to satisfy this requirement. By posting RMX

records, a domain declares that it has adopted the necessary measures.

Will it stop spam?

No, but it will help. The stated goal is to give system admins a way to

prevent malicious misuse of their names by spammers, and it does accomplish

that. However, by giving intelligent tools like spamassassin more

information to work with, it will help to reduce spam, particularly as the

number of RMX-protected sites grows. Because RMX

is such a simple concept (particularly for the recipient), it stands a much

better chance of being adopted than some of the more complicated proposals.

Furthermore, RMX helps against spam by making compromised,

poorly-secured machines--most connected home desktop machines fall into this

category--less useful as spam tools. Spammers often trick these machines

into sending spam for them. RMX does not stop this practice,

but it makes spammers unable to claim that the messages originated from any

RMX-protected domain, since otherwise the messages would be

treated as forgeries by their recipients. This property is more useful than

it would first seem, as we shall now show.

Suppose that you are a responsible domain administrator, and further suppose the owner of a compromised home desktop computer uses your email service. In this situation, many anti-forgery proposals break; the spammer could steal the desktop owner's credentials and begin spamming as him or her immediately. Since your domain name is attached to his or her email address, this abuse could affect you; in some cases it will lead to your domain being blacklisted.

With RMX, however, the spammer can still steal credentials,

but to make the messages legit he must send them through your mail servers.

Being a responsible domain administrator, you have automated tools that

detect and flag attempts by a single user to send a lot of messages at once,

and cut that user off (with a message like this)

until the situation is resolved. Thus, the spammer cannot get away with

sending a large number of spams appearing to come from your domain;

RMX has given you both the ability and the responsibility to

secure your domain.

What are the implications for .forward?

Suppose Bob, upon graduating from foo.edu, opens an account

with emailprovider.com. It is common practice for Bob to put a

.forward file in his old foo.edu account, which

tells it to forward mail to the new account.

Now suppose emailprovider.com wants to start checking

RMX records. What happens? If foo.edu has an

old mail server which doesn't do sender rewriting, then

emailprovider.com will see messages claiming to be from

original senders but forwarded from foo.edu, and will conclude

that the messages are forgeries.

How should this situation be handled? Well, ideally, foo.edu

should update its mail server, but we can't count on that happening. In the

meantime, the best course of action for emailprovider.com is to

not reject apparently-forged email, but to pass it to the

client with an X-header noting that the RMX

check failed. This gives Bob the option of accepting mail that arrives from

the foo.edu mail servers addressed to his old address even if

it does not pass RMX muster.

It is for this reason, and for certain situations involving mailing lists

and anonymous senders, that I believe bouncing messages immediately--or even

during the SMTP session, as has been proposed--would be a bad idea. Better

to pass the information in an X-header, and let the

client/spamfilter sort it out, at least during the transition period. I

acknowledge that this position puts me at odds with RFC-2505.

Is spam really forged?

How much of spam is really forged? Here's one clue. David Walker sent the following breakdown of spam he received to IETF's anti-spam research group:

With regards to spoofing being a minor problem. Out of 3130 denied messages (to accounts I had to stop because they were receiving 100% spam) @juno.com | 36 @netscape.com | 38 @email.com | 40 @excite.com | 50 @lycos.com | 50 @earthlink.net | 71 @msn.com | 72 @yemenmail.com | 93 @hotmail.com | 241 @aol.com | 298 @yahoo.com | 311 Total | 1300 1300 out of 3130 = 41% of all my denies are very high likelyhood spoofs from the popular domains 1050 out of 3130 = 34% are guaranteed spoofs (The helo name is not remotely associated with the spoofed domain) from the popular domains. (These numbers do not represent all spoofing I receive but rather just the spoofing to popular domains)

The FTC also reports in their2003 study [pdf] on misleading information in spam that "one-third of the spam messages contained false text in the From line." Thanks to Phill Hallam-Baker for referring me to this article.

What about the RFC-822 From: header?

Daniel Erat raises a very reasonable and interesting point. We have shown

that by using RMX, a domain may prevent its name from being

forged on the email envelope (the MAIL FROM address of

RFC-821). However, a lot of mail reading programs do not show the

envelope header; they show only the From: address given inside

the message (RFC-822). So we've succeeded in making the envelope return

address trustworthy, but in many cases the butler is throwing out the

envelope before passing the message to the recipient!

This fact does remove one incentive for senders to implement

RMX records--right now, recipients might not notice. On the

other hand, forgeries will still be obvious to automated filters, vacation

programs, and such. Once RMX is implemented, the true meaning

of the envelope MAIL FROM will be "he who forwarded this

message to you" and the message From: will be "where the

message claims to have originated." The two may differ; for example, in the

case of a mailing list, the envelope return address is that of the list but

the internal From: is that of the original sender. As

RMX records become widespread, hopefully mail reader software

will evolve to show recipients both pieces of information in a way that

makes their meanings clear.

DNS spoofing issues

Roger Standridge (homepage) and your author had a long discussion about this issue. In its current form, DNS is known to be vulnerable to certain types of spoofing and cache poisoning attacks. Joe Stewart has a very informative article on this topic, which you can find at Security Focus.

RMX is particularly sensitive to this problem. Because an

attacker controls the timing of RMX requests--by choosing when

to send forged email--he or she knows when to send spoofed DNS replies.

Turns out this has already been

mentioned before. However, in most cases the attacker already has this

advantage for other reasons. Recursive queries, reverse-lookups on incoming

mail, and honeypot-based techniques could all be used to give the attacker

much the same advantage. In the end, RMX gives the MAIL

FROM domain the same level of trust as the URL in a web

browser, which is to say, not much right now.

When upgrading to an RMX-aware mail server or posting

RMX records, administrators must also verify that their name

servers are up to date and properly configured, or the RMX

check will be essentially meaningless. Once DNSSEC becomes

widespread, this problem will be less of an issue.

Privacy issues

All email leaving an RMX-protected domain must pass through one

of its designated mail servers to be certified as a non-forgery. This

property was a design goal. One oft-raised objection, though, is that it

gives a domain owner the ability to filter outgoing mail, should he or she

wish.

While I agree that this technically true, I do not agree that it is a problem. Consider the following:

- It is already possible for an ISP or company to filter outbound mail

(since it can filter outbound port-25 TCP connections); there's nothing

really new here. So far as I understand, most companies and ISP's do not

currently filter outbound email, so there is no reason to believe they will

begin filtering it when they switch to

RMX. - Organizations which choose to filter will filter, and those which choose to not filter will not. This is a decision which can be left to the organization and documented in its privacy policy.

- If a sender is unhappy with an email provider's policy, he or she may switch to any other willing email provider on the Internet. A sender may even operate his or her own domain. In contrast, working around the already-possible ISP filtering could be more difficult.

- Incoming mail already passes through designated (via

MX) mail servers. Why should outgoing mail be different? - Email is already known to be a fundamentally insecure medium.

Note that cryptography-based alternatives have been proposed which claim to afford more privacy at the cost of somewhat more disruptive changes.

The Joe Job

The act of destroying a person's online reputation by sending spam claiming to come from him or her is called a Joe Job. Joe Jobbers are con artists--they aren't trying to sell something, they're trying to smear someone. It is important to recognize the difference; next time you become furious with someone who apparently sent you an offensive spam, realize that he or she may be the innocent victim of a Joe Job. For an interesting discussion, see this article. Brian T Glenn was kind enough to send me information about the origin of the term: here is a page from the person who coined it, and a a newsgroup discussion on the topic.

Issues for users of dyndns

In response to the IPv4 address shortage, the fact that home users do not run servers, and a general desire to keep things plug-n-play, most home and small-business ISP's offer only temporary, DHCP-assigned IP addresses to their clients. This is a problem for the small body of homes and businesses that do wish to run their own servers on such systems, since they need a permanent way to refer to their machines from outside. Under dyndns, or Dynamic DNS, the home or small business registers a permanent domain name, and obtains name service from a special DNS provider that responds very quickly (and automatically) to changes in the host's IP address, and keeps the cache time very small.

If a dyndns user wishes to implement RMX, he or she may need to

update the appropriate RMX record dynamically along with the

usual A record. Note that it is not currently necessary to

change MX records under dyndns, because they point to

A records indirectly, through CNAMEs. Under

RMX, several field types are possible (see Hadmut's draft for

the proposed types). Some would need to be dynamically updated, and others

(which provide a level of indirection though a permanent name) would not.

Thanks to Tim Long for pointing this issue

out to me.

I use [popular webmail site] though a web-to-pop3

interface such as hotwayd because I don't like to use the web

interface directly; will RMX break my system?

Possibly; this is a complicated issue.

If your email provider allows non-web-based access and decides to post

RMX records, then it must provide a way for you to send email

(SMTP) as well as receive it (POP3 or IMAP), or recipients will refuse to

accept your mail. There are a few providers out there--Hotmail in

particular--which do not explicitly prohibit non-web-based access, but at

the same time provide only a nonstandard way to access it. And there are a

number of workarounds for this problem, such as the hotwayd project. If

Hotmail decides to post RMX records, then it will either

provide remote access through (e.g.) secure SMTP-AUTH, provide

remote access through some kind of nonstandard protocol which can be worked

around (such as a web form), or change the terms of service to prohibit

non-web-based access.

If your webmail provider refuses to permit non-web-based access, then you

will have to use their web interface or switch to a different provider. If

it opts to permit non-web-based access but provides only a nonstandard way

to send mail, then projects such as hotwayd will need to

develop a workaround, and users of such projects will need to use the web

interface to send mail until the needed tools are ready. Such users also

have the option of sending from a different (but also legitimate) address

and including an appropriate Reply-to: header.

If your email provider allows secure SMTP-AUTH access, then

you're set, unless your ISP refuses to allow outbound TCP port 465

connections. In this last case, you'll need to convince your ISP to unblock

port 465 connections to your email provider or find a less brain-dead ISP.

A somewhat more common problem would be ISP's blocking outbound TCP port 25

connections; webmail providers should keep this issue in mind when

configuring their remote access systems. It would be best to explicitly

allow SMTPS access, which has vast security advantages over

unencrypted SMTP-AUTH anyway.

Please understand that sending MAIL FROM a machine which is not

authorized to send from that domain is a benevolent form of forgery--one

which is indistinguishable from its less innocuous cousins. If we want to

end forgery, then benevolent forgery must also go. It is becoming

increasingly common for recipients to block email from popular domains when

the emails do not arrive directly from the domains' mail servers; see, for

example, the system described here.

This is a manual form of RMX, applied to only a few popular and

frequently-forged domains. It can be a problem, though, because it blocks

some legitimate uses, such as the hotwayd workaround described

above. RMX suffers no such problem; by posting

RMX records, a domain declares that it has already provided all

of the remote access facilities that it intends to provide, and that

therefore any other email claiming to come from it should be treated as a

forgery.

By the way, if you work for Hotmail, Yahoo mail, AOL, or one of the other

major providers, I'd be very interested to hear whether your company

intends to implement RMX, and if so, how it intends to handle

remote access.

Thanks to RenE J.V. Bertin for bringing up this issue.

Epilogue

When I originally wrote this document in late February 2003, I intended to

call the new records MO, for "mail origin." I began to write

an Internet Draft to the IETF to formally propose the new method at the same

time I wrote this page to bring it to the general public. In the process of

finding references, however, I stumbled upon Hadmut Danisch's draft,

which proposed essentially the same thing, but called the new records

RMX instead of MO. I'd been scooped! I contacted

Hadmut to explain the situation, and suggested that I post this page (since

it was already mostly written!) in support of RMX records

instead. Hadmut was kind enough to reply, and he agreed with the

suggestion.

RMX records are a simple, practical, and elegant solution that

should have been implemented a long time ago. To make them happen, the

following changes need to take place:

- Hadmut's Internet-Draft needs to become a real RFC (this process is already well under way; the rest can happen concurrently).

- The

RMXresource record must be added toDNSsoftware such as bind. RMXchecks must be added to mail server software such as sendmail and postfix.- Admins need to start using them!

Update (2003.06.01): Hadmut has released first bind9 and sendmail implementations. See his site to download the patches.

With this document, I hope to accelerate the process a bit, by making people

aware of the existence and potential benefits of RMX records.

I hope you'll agree that now is the time to make this happen--but if you

disagree, I'd like to hear that, too. Please feel free to write to me at the

address below (webmaster) with comments.

--Mike

References

- Hadmut Danisch's Internet Draft, which will hopefully soon be an RFC

- Danisch's draft has a permanent home (along with updates) here

-

G. Fecyk has written a draft

proposing a very similar solution. Under Fecyk's scheme, the recipient

actually queries the

From:nameserver with the IP address from which it received an email, rather than requesting the list and making the decision itself. This is slightly more complicated and hits DNS harder, but has advantages too. An organization would quickly detect the source of attempts to forge its name, and there would be no need to add an additionalRR(just a new convention). I would be equally satisfied with this solution to the forgery problem. Thanks to Scott Nelson for pointing this out to me. -

Paul Vixie has written Repudiating

MAIL FROM, a proposal which accomplishes basically the same thing as

RMXby overloadingMXrecords instead. I like this approach as well; it has the same net effect asRMXwithout introducing the additional resource record. Notice, however, that it might hit DNS harder. -

Meng Weng Wong has proposed a hybrid

between Fecyk's

DMPand Danisch'sRMX. His page also has a good discussion and comparisons of the two proposals, worth reading. - David Green proposed essentially the same idea way back in 2002! He has a page about it here. And he notes that Paul Vixie mentions that Jim Miller suggested the concept as early as 1998!

- RFC 821: Simple Mail Transfer Protocol [describes the protocol used in email]. 1982.

- RFC 974: Mail Routing and the Domain System [describes how email and DNS interact]. 1986.

- RFC 1035: Domain Names - Implementation and Specification [describes the operation of DNS and RRs]. 1987.

- RFC 2505: Anti-Spam Recommendations for SMTP MTA's. 1999. This document is also known as BCP-30 because it documents best current practices.

- RFC 2535: Domain Name System Security Extensions [describes DNSSEC]. 1999.

- ASRG, the IETF anti-spam research group.

- spamassassin, a powerful filtering tool.

- whois.net, a public whois service. Notice that most UNIX-like systems have a command-line whois utility built-in.

- My original posting to the IETF's anti-spam research group, which spawned a lot of good discussion, for and against--and a surprising amount of FUD.

| © Rubel 2004 | About this site |